PulseAudio under the hood

Table of contents

- Preface

- About PulseAudio

- High-level components

- Key abstractions

- D-Bus API

- C API

- Protocols and networking

- Device drivers

- Sound processing

- Sample cache

- Stream management

- Time management

- Power saving

- Automatic setup and routing

- Desktop integrations

- Compatibility layers

- Server internals

- Module list

- GUI tools

- Command line tools

- Configuration

- Portability

- Example setups

- Example clients and modules

- Critique

Preface

I’m working on the Roc Toolkit open-source project, a development kit for realtime audio streaming over the network. You can read more about the project in these two articles: 1, 2.

We decided to implement a set of PulseAudio modules that will allow PulseAudio to use Roc as a network transport. Many Linux distros employ PulseAudio, and their users will be able to improve network service quality without changing the workflow. This led me to dig into PulseAudio internals and eventually to this document.

Motivation

PulseAudio has Documentation page covering many specific problems that may be encountered by user and developer. Modules page contains a complete list of existing modules with parameters. D-Bus API and C API are also documented well.

Unfortunately, the available documentation doesn’t give a bird-eye view and an explanation of PulseAudio features and design and doesn’t cover many implementation details.

In result, the overall picture remains unclear. Advanced configuration looks mysterious because one need to understand what happens under the hood first. The learning curve for the module writer is high too.

This document tries to fill the gap and provide an overview of the PulseAudio features, architecture, and internals. More precisely, it has three goals:

- describe the available features

- explain their underlying design and important implementation details

- provide a starting point for writing clients and server modules

It does not provide a detailed reference or tutorial for PulseAudio configuration and APIs. Further details can be obtained from the official documentation (for configuration and client APIs) and from the source code (for internal interfaces).

Disclaimer

I’m not a PulseAudio developer. This document reflects my personal understanding of PulseAudio, obtained from the source code, experiments, official wiki, mailing lists, and blog articles. It may be inaccurate. Please let me know about any issues.

PulseAudio tends to trigger flame wars, which I believe are non-constructive. This document tries to be neutral and provide an unbiased overview of the implemented features and design.

Thanks

I’d like to thank my friends and colleagues Mikhail Baranov and Dmitriy Shilin who read early drafts of the document and provided a valuable feedback.

Also big thanks to Tanu Kaskinen, a PulseAudio maintainer, who have found and helped to fix dozens of errors.

They all definitely made it better!

Meta

This document was last updated for PulseAudio 11.1.

Last major update: 21 Oct 2017.

About PulseAudio

PulseAudio is a sound server for POSIX OSes (mostly aiming Linux) acting as a proxy and router between hardware device drivers and applications on single or multiple hosts.

See details on the About page on wiki.

Design goals

PulseAudio is designed to meet a number of goals.

-

Abstraction layer for desktop audio

PulseAudio manages all audio applications, local and network streams, devices, filters, and audio I/O. It provides an abstraction layer that combines all this stuff together in one place.

-

Programmable behavior

A rich API provides methods for inspecting and controlling all available objects and their both persistent and run-time properties. This makes it possible to replace configuration files with GUI tools. Many desktop environments provide such tools.

-

Automatic setup

PulseAudio is designed to work out of the box. It automatically detects and configures local devices and sound servers available in the local network. It also implements numerous policies for automatic audio management and routing.

-

Flexibility

PulseAudio provides a high flexibility for the user. It’s possible to connect any stream of any application to any local or remote device, configure per-stream and per-device volumes, construct sound processing chains, and more.

-

Extensibility

PulseAudio provides a framework for server extensions, and many built-in features are implemented as modules. Non-official third-party modules exist as well, however, the upstream doesn’t provide a guarantee of a stable API for out-of-tree modules.

Feature overview

The following list gives an idea of the features implemented in PulseAudio.

-

Protocols and networking

PulseAudio supports a variety of network protocols to communicate with clients, remote servers, and third-party software.

-

Device drivers

PulseAudio supports several backends to interact with hardware devices and controls. It supports hotplug and automatically configures new devices.

-

Sound processing

PulseAudio implements various sound processing tools, like mixing, sample rate conversion, and acoustic echo cancellation, which may be employed manually or automatically.

-

Sample cache

PulseAudio implements an in-memory storage for short named batches of samples that may be uploaded to the server once and then played multiple times.

-

Stream management

PulseAudio manages all input and output streams of all desktop applications, providing them such features as clocking, buffering, and rewinding.

-

Time management

PulseAudio implements a per-device timer-based scheduler that provides clocking in the sound card domain, maintains optimal latency, and reduces the probability of playback glitches.

-

Power saving

PulseAudio employs several techniques to reduce CPU and battery usage.

-

Automatic setup and routing

PulseAudio automatically sets parameters of cards, devices, and streams, routes streams to devices, and performs other housekeeping actions.

-

Desktop integrations

PulseAudio implements several features that integrate it into the desktop environment.

-

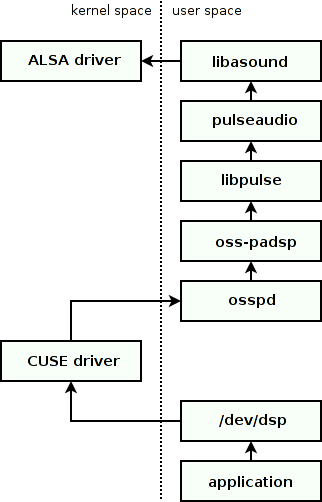

Compatibility layers

There are several compatibility layers with other sound systems, so that existing applications may automatically run on top of PulseAudio without modification.

Use cases

Here are some practical examples of how PulseAudio features may be used on the desktop:

-

Smart hotplug handling. For example, automatically setup Bluetooth or USB headset when it’s connected, or automatically switch to headphones when they’re inserted into the jack.

-

A GUI for easy switching an audio card between various modes like stereo, surround, or S/PDIF.

-

A GUI for easy switching an audio stream to any available audio device, like internal speakers, wired headphones, Bluetooth headset, or HDMI output.

-

A GUI for making a single application louder than others, or muting it, and remembering this decision when the application will appear next time.

-

A GUI for routing audio to a remote device available in LAN. For example, connecting a browser playing music on a laptop to speakers attached to a Raspberry Pi.

-

Automatically routing music or voice from a Bluetooth player or mobile phone to a sound card or Bluetooth speakers or headset.

-

Transparently adding various sound processing tools to a running application, for example adding acoustic echo cancellation to a VoIP client.

-

Reducing CPU and battery usage by automatically adjusting latency on the fly to a maximum value acceptable for currently running applications, and by disabling currently unnecessary sound processing like resampling.

-

Smart I/O scheduling, which may combine a high latency for playback (to avoid glitches and reduce CPU usage) and a low latency for user actions like volume changes (to provide smoother user experience).

-

Automatically integrating existing desktop applications into PulseAudio workflow, even if they are not aware of PulseAudio.

Problems and drawbacks

There are several known disadvantages of using PulseAudio, including both fundamental issues, and implementation issues that may be resolved in the future:

- additional complexity, overhead, and bugs (more code always means more bugs)

- lack of comprehensive documentation

- non-intuitive command line tools and configuration

- weird features like autospawn and built-in watchdog

- higher minimum possible latency

- poor quality of service over an unreliable network like 802.11 (WiFi)

- no hardware mixing and resampling

- no hardware volumes when using ALSA UCM

High-level components

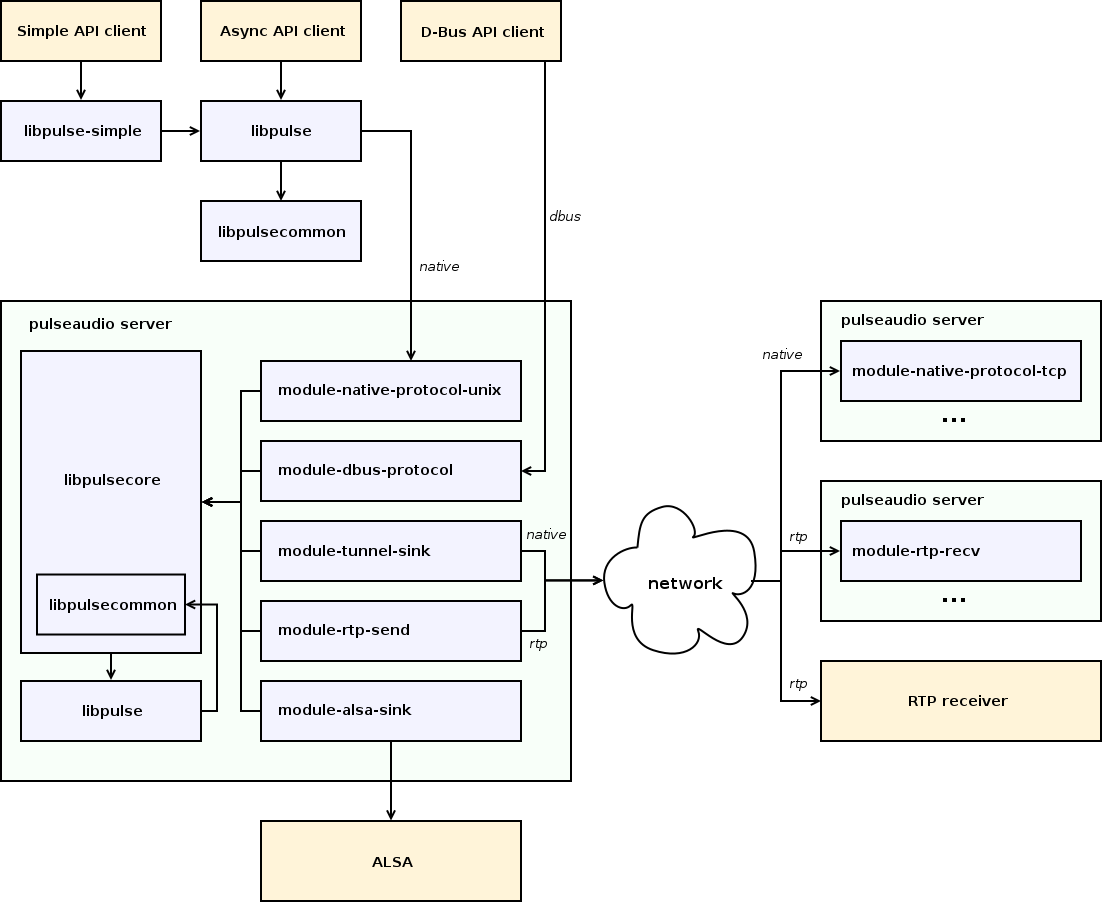

The diagram below demonstrates a simplified view of an example PulseAudio setup.

It shows three clients (employing three different APIs), one local PulseAudio server, two remote PulseAudio servers (connected via “native” and RTP protocols), one remote RTP receiver, ALSA backend, and a set of modules required to serve this setup.

The diagram shows most important PulseAudio components:

-

libpulse-simple

Client library.

Provides “Simple API” for applications. Implemented as a wrapper around libpulse.

-

libpulse

Client and server library.

Provides “Asynchronous API” for applications. Communicates with the server via the “native” protocol over a Unix domain or TCP stream socket.

Contains only definitions and code that are part of public API. The server also reuses definitions and some code from this library internally.

-

libpulsecommon

Client and server library.

Contains parts from libpulsecore which are needed on both client and server but can’t be included into libpulse because they are not part of public API. For technical reasons, it also contains parts of libpulse.

-

libpulsecore

Server library.

Provides internal API for modules. Contains common environment and generic building blocks for modules.

-

modules

Server extensions.

Many server features are implemented in modules, including network protocols, device drivers, desktop integrations, etc.

Key abstractions

This sections discusses the key server-side object types.

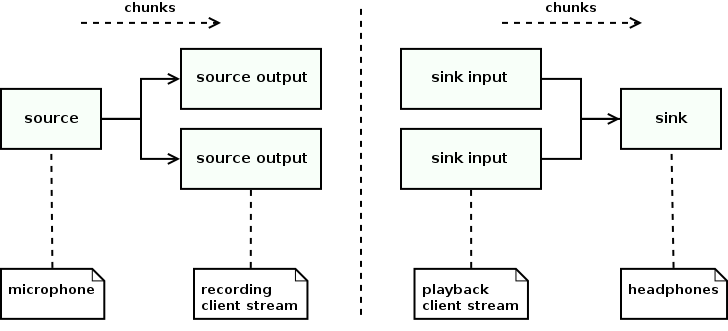

Devices and streams

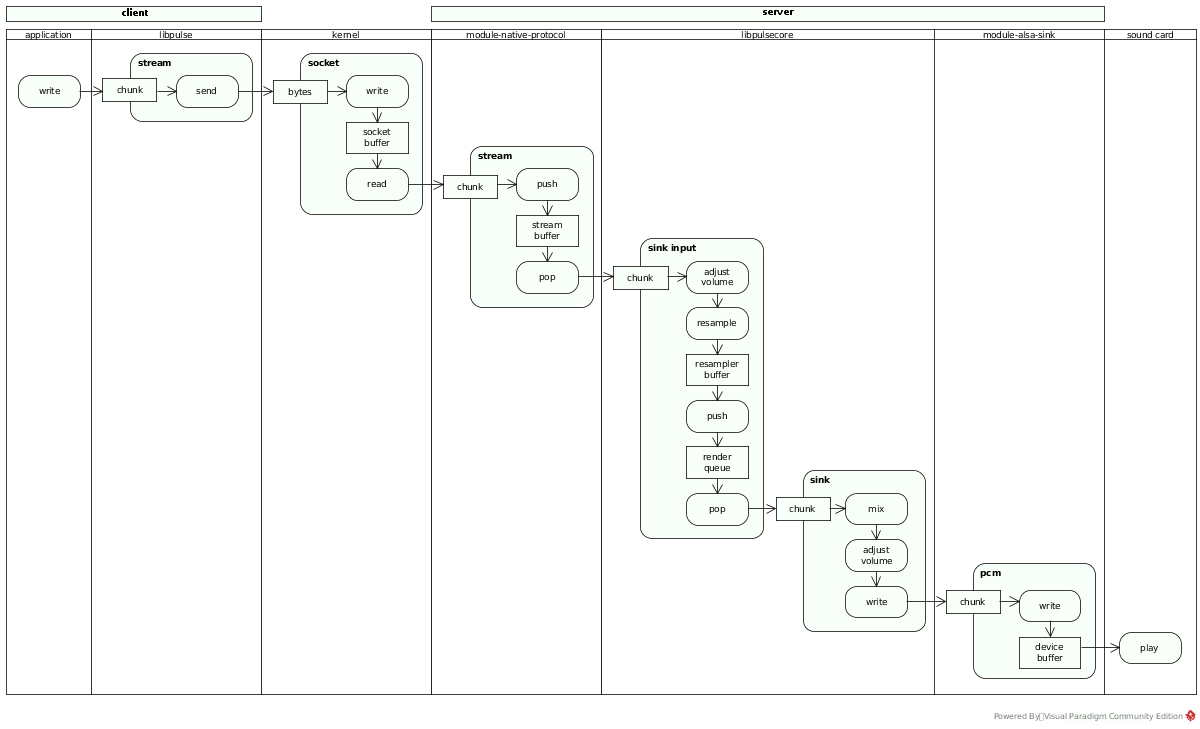

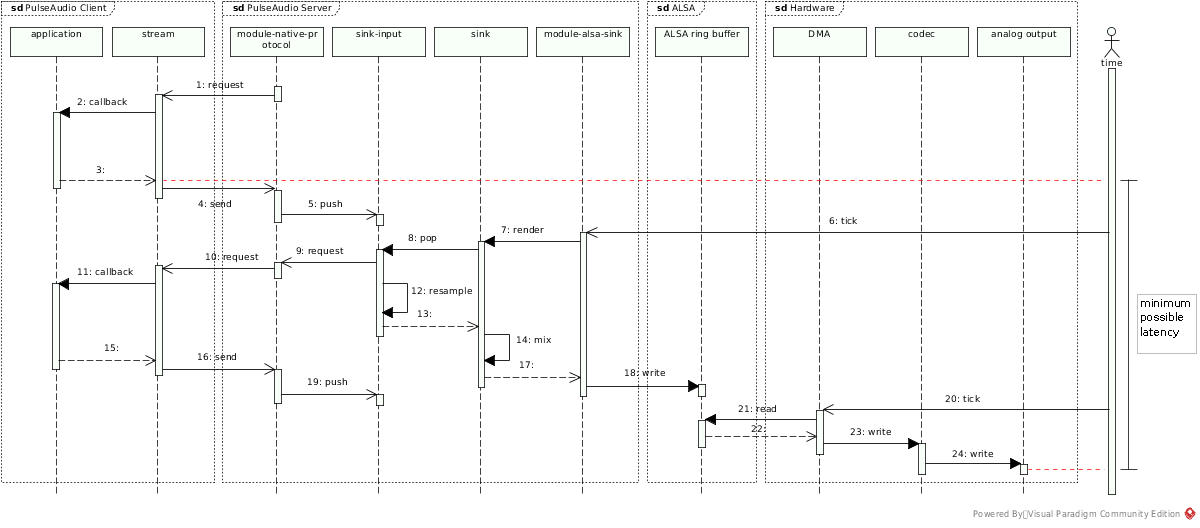

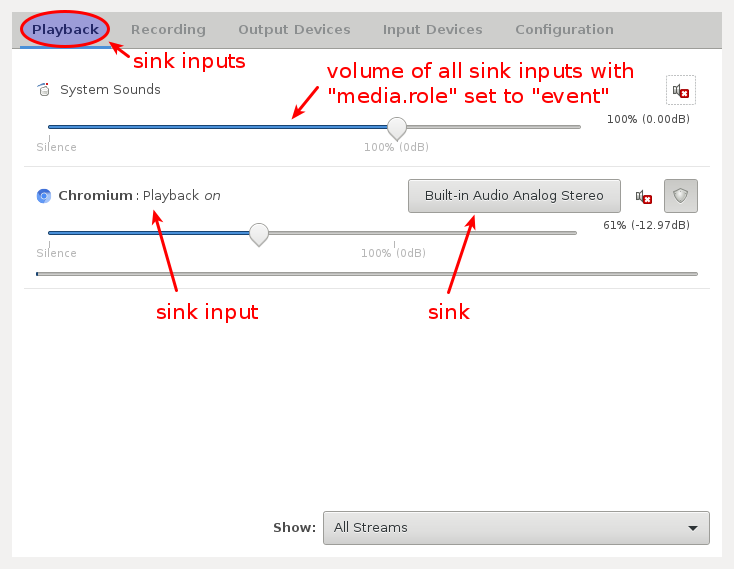

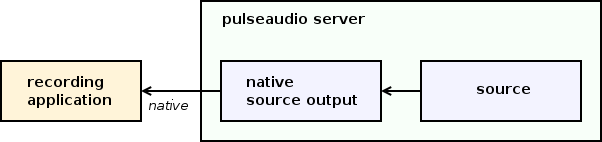

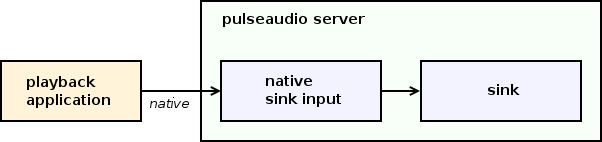

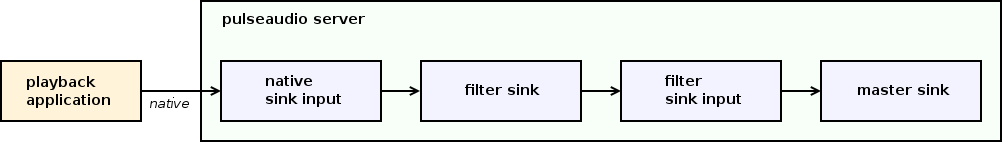

PulseAudio is built around devices (sources and sinks) connected to streams (source outputs and sink inputs). The diagram below illustrates these connections.

-

Source

A source is an input device. It is an active unit that produces samples.

Source usually runs a thread with its own event loop, generates sample chunks, and posts them to all connected source outputs. It also implements clocking and maintains latency. The rest of the world usually communicates with a source using messages.

The typical source represents an input sound device, e.g. a microphone connected to a sound card line input or on a Bluetooth headset. PulseAudio automatically creates a source for every detected input device.

-

Source output

A source output is a recording stream. It is a passive unit that is connected to a source and consumes samples from it.

The source thread invokes source output when next sample chunk is available or parameters are updated. If the source and source output use different audio formats, source output automatically converts sample format, sample rate, and channel map.

The typical source output represents a recording stream opened by an application. PulseAudio automatically creates a source output for every opened recording stream.

-

Sink

A sink is an output device. It is an active unit that consumes samples.

Sink usually runs a thread with its own event loop, peeks sample chunks from connected sink inputs, and mixes them. It also implements clocking and maintains latency. The rest of the world usually communicates with a sink using messages.

The typical sink represents an output sound device, e.g. headphones connected to a sound card line output or on a Bluetooth headset. PulseAudio automatically creates a sink for every detected output device.

-

Sink input

A sink input is a playback stream. It is a passive unit that is connected to a sink and produces samples for it.

The sink thread invokes sink input when next sample chunk is needed or parameters are updated. If sink and sink input use different audio formats, sink input automatically converts sample format, sample rate, and channel map.

The typical sink input represents a playback stream opened by an application. PulseAudio automatically creates a sink input for every opened playback stream.

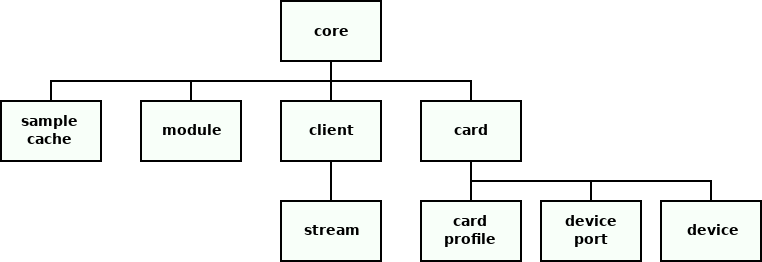

Object hierarchy

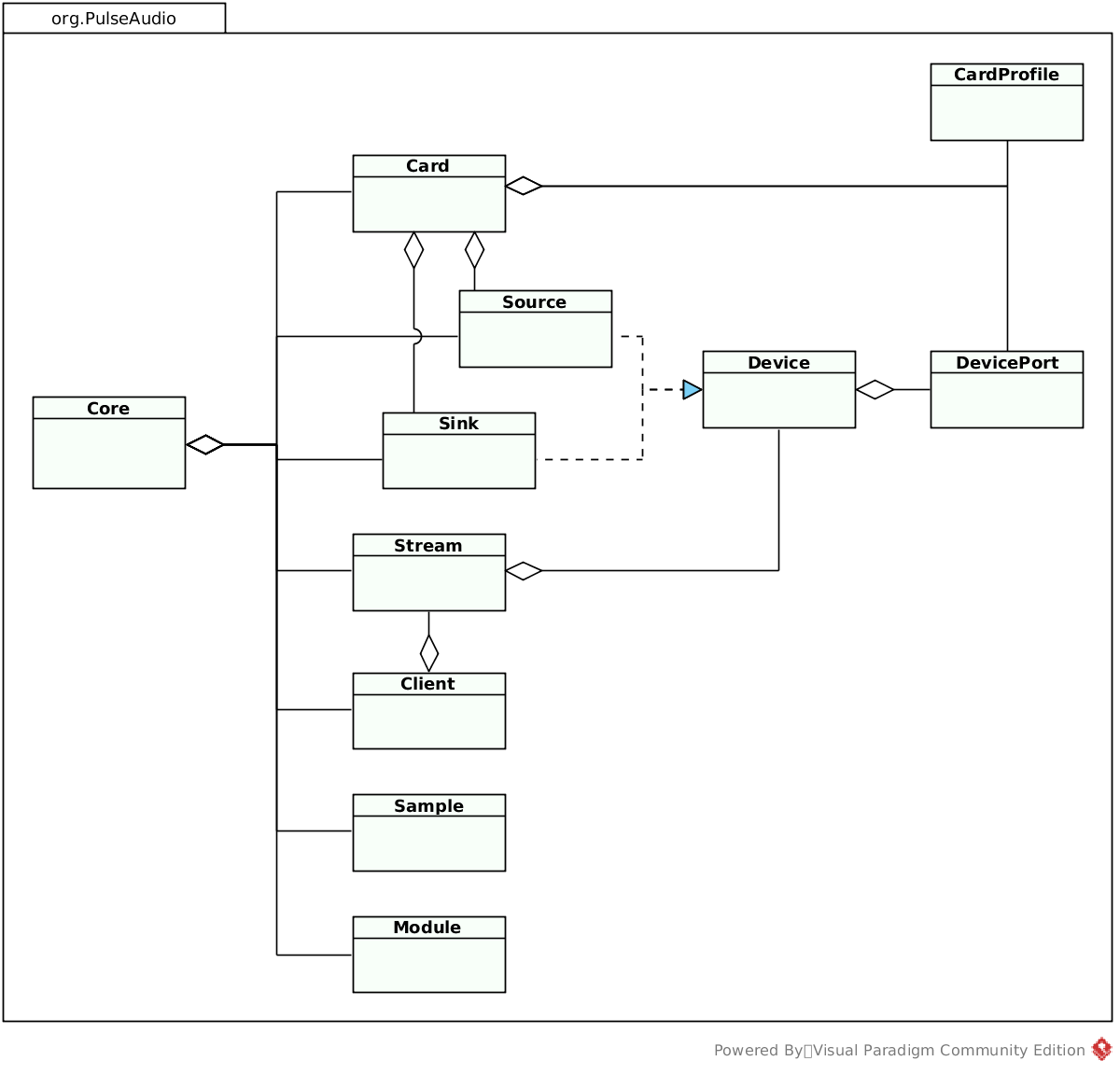

The diagram below shows the hierarchy of the server-side objects.

-

Core

The core provides a shared environment for modules. Modules use it to find and register objects, install hooks for various events, register event loop handlers, etc.

There is only one core instance which is created at startup.

-

Module

A module represents a loadable server extension.

Modules usually implement and register other objects. A module can be loaded multiple times with different parameters and so have multiple instances.

The typical module implements a network or device discovery, a network or hardware device or stream, or a sound processing device. For example, PulseAudio loads a new instance of the module-alsa-card for every detected ALSA card.

-

Client

A client represents an application connected to the PulseAudio server.

It contains lists of playback and recording streams.

The typical client represents a local application, e.g. a media player, or a remote PulseAudio server. PulseAudio automatically creates a client for every incoming connection.

-

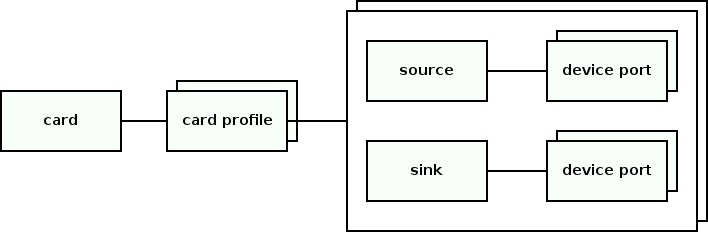

Card

A card represents a physical audio device, like a sound card or Bluetooth device.

It contains card profiles, device ports, and devices (sources and sinks) connected to device ports. It also has a single active card profile.

The typical card represents ALSA card or Bluetooth device. PulseAudio automatically creates a card for every detected physical device.

-

Card profile

A card profile represents an opaque configuration set for a card.

It defines the backend-specific configuration of the card, and the list of currently available devices (sources and sinks) and device ports. Only one card profile of a card may be active at the same time. The user can switch the active card profile at any time.

The typical card profile represents the sound card mode, e.g. analog and digital output, and mono, stereo, and surround mode. PulseAudio automatically creates a card profile for every available operation mode of a card.

-

Device port

A device port represents a single input or output port on the card.

A single card may have multiple device ports. Different device ports of a single card may be used simultaneously via different devices (sources and sinks).

The typical device port represents a physical port on a card, or a combination of a physical port plus its logical parameters, e.g. one output port for internal laptop speakers, and another output port for headphones connected via a line out. PulseAudio automatically creates device ports for every detected card, depending on the currently active card profile.

-

Device

A device represents an active sample producer (input device) or consumer (output device).

A device can have an arbitrary number of streams connected to it. A recording stream (source output) can be connected to an input device (source). A playback stream (sink input) can be connected to an output device (sink).

There are three kinds of devices:

-

Hardware device

Hardware source or sink is associated with an audio device. Usually, it is explicitly associated with a card object, except those limited backends that don’t create card objects.

Such sources and sinks contain a subset of device ports provided by the device and have a single active device port, from which they will read or write samples. The user can switch the active device port of a source or sink at any time.

PulseAudio automatically creates one or several pairs of a hardware source and sink for every detected card, depending on the currently active card profile.

-

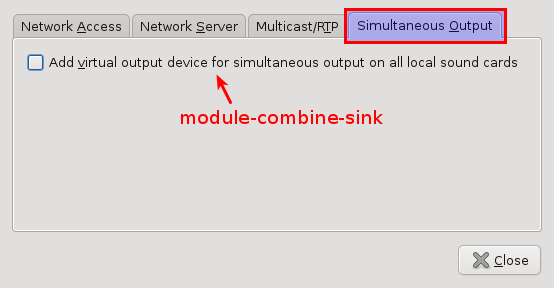

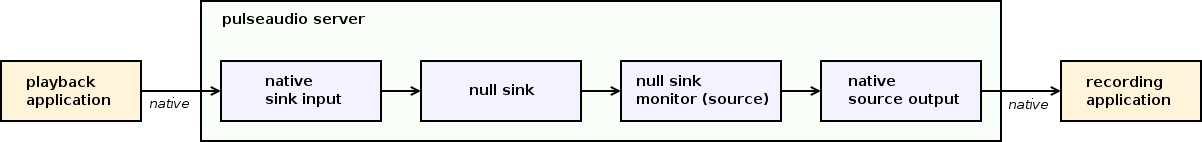

Virtual device

Virtual source or sink is not associated with an audio device. It may represent a remote network device, a sound processing filter, or anything else, depending on the implementation.

PulseAudio may automatically create a pair of virtual source and sink for every remote sound card exported by every PulseAudio server in the local network.

-

Monitor device

Sink monitor is a special kind of virtual source associated with a sink.

Every sink automatically gets a sink monitor, named as “<sink_name>.monitor”. Every time when the sink reads a chunk from its sink inputs, it also writes this chunk to the sink monitor.

Typical usage of the sink monitor is capturing all sound that was sent to speakers and duplicating it somewhere else. PulseAudio automatically creates a sink monitor for every sink.

-

-

Stream

A stream represents a passive sample consumer (recording stream) or producer (playback stream).

Every stream should be connected to some device. A recording stream (source output) should be connected to an input device (source). A playback stream (sink input) should be connected to an output device (sink).

There are two kinds of streams:

-

Application stream

An application stream is associated with a client. It is created when an application connected to PulseAudio server starts playback or recording.

-

Virtual stream

A virtual stream is not associated with a client. It may represent a remote network server or anything else, depending on the implementation.

-

-

Sample cache

The sample cache is an in-memory storage for short named batches of samples that may be uploaded to the server once and then played multiple times. It is usually used for event sounds.

D-Bus API

PulseAudio server-side objects may be inspected and controlled via an experimental D-Bus API. Note that it can’t be used for playback and recording. These features are available only through the C API.

Unfortunately, the D-Bus API has never left the experimental stage, and it has no stability guarantees and is not actively maintained. Applications are generally advised to use the C API instead.

Buses and services

D-Bus has several modes of communication:

- via a system bus (system-wide)

- via a session bus (one bus per login session)

- peer-to-peer (direct communication between applications)

PulseAudio implements several D-Bus services:

- Device reservation API (on session bus)

- Server lookup API (on session bus)

- Server API (peer-to-peer)

- Server API extensions (peer-to-peer)

Device reservation API

Device reservation API provides methods for coordinating access to audio devices, typically ALSA or OSS devices. It is used to ensure that nobody else is using the device at the same time.

If an application needs to use a device directly (bypassing PulseAudio), it should first acquire exclusive access to the device. When access is acquired, the application may use the device until it receives a signal indicating that exclusive access has been revoked.

This API is designed to be generic. It is a small standalone D-Bus interface with no dependencies on PulseAudio abstractions, so it may be easily implemented by other software.

Server lookup API

PulseAudio server API uses peer-to-peer D-Bus mode. In this mode, clients communicate directly with the server instead of using a session bus, which acts as a proxy. In contrast to the session bus mode, this mode permits remote access and has lower latency. However, clients need a way to determine the server address before connecting to it.

To solve this problem, PulseAudio server registers server lookup interface on the session bus. A client should first connect to the session bus in order to discover PulseAudio server address and then connect to PulseAudio server directly for peer-to-peer communication.

Server API

Server API is available through a peer-to-peer connection to PulseAudio server.

Every object in the hierarchy is identified by a unique path. The hierarchy starts with the core object, which has a well-known path. It may be used to discover all other objects.

The diagram below shows the most important D-Bus interfaces.

-

Core - A top-level interface that provides access to all other interfaces.

-

Module - A loadable server extension.

-

Client - An application connected to the PulseAudio server.

-

Card - A physical audio device, like a sound card or Bluetooth device.

-

CardProfile - An opaque configuration set for a card.

-

DevicePort - A single input or output port on the card.

-

Device - The parent interface for Source and Sink.

-

Source - An input device. May be associated with a card and device port.

-

Sink - An output device. May be associated with a card and device port.

-

Stream - May be either a recording stream (source output) or playback stream (sink input). Application stream is associated with a client.

-

Sample - A named batch of samples in the sample cache.

In addition to the core interface, PulseAudio modules can register custom server API extensions, that are also discoverable through the core. Several extensions are available out of the box:

-

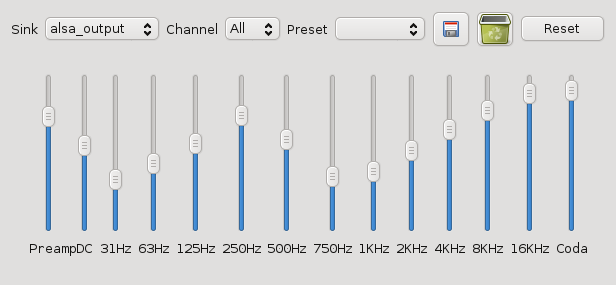

StreamRestore

componentmodule-stream-restoreQuery and modify the database used to store device and stream parameters.

-

Equalizer

componentmodule-equalizer-sinkQuery and modify equalizer sink levers.

-

Ladspa

componentmodule-ladspa-sinkQuery and modify LADSPA sink control ports.

C API

PulseAudio provides C API for client applications.

The API is implemented in the libpulse and libpulse-simple libraries, which communicate with the server via the “native” protocol. There are also official bindings for Vala and third-party bindings for other languages.

C API is a superset of the D-Bus API. It’s mainly asynchronous, so it’s more complex and harder to use. In addition to inspecting and controlling the server, it supports recording and playback.

The API is divided into two alternative parts:

- Asynchronous API (libpulse), complicated but complete

- Simple API (libpulse-simple), a simplified synchronous wrapper for the recording and playback subset of the asynchronous API

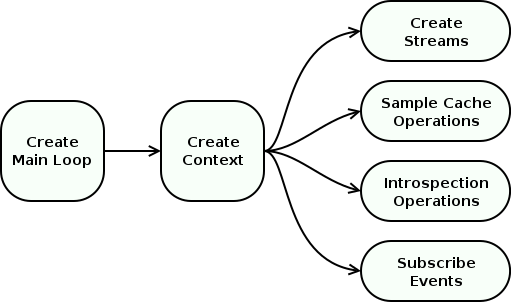

Asynchronous API

Asynchronous API is based on event loop and callbacks.

The diagram below demonstrates the workflow.

-

Main Loop

The first step is creating an instance of one of the available Main Loop implementations. They differ in a way how the user can run the main loop: directly, in a separate thread, or using Glib.

All communications with the server happen inside the main loop. The user should run main loop iterations from time to time. The user can either register callbacks that are invoked from the main loop or use polling.

For a regular main loop, polling may be performed between iterations. For a threaded main loop, polling may be performed after obtaining a lock from another thread.

-

Context

The second step is creating a Context object that represents a connection to the server. The user can set callbacks for context state updates.

-

Stream

When context state becomes ready, the user can create one or multiple Stream objects for playback or recording.

The user can set callbacks for stream state updates and I/O events, invoked when the server wants to send or receive more samples. Clocking is controlled by the server. Stream also provides several management functions, like pause, resume, and volume control.

-

Sample Cache

In addition to regular streams, the user can also use Sample Cache to upload named batches of samples to the server without playing them and start playback later.

-

Introspection

Having a context in a ready state, Server Query and Control API may be used to query and modify various objects on the server. All operations are asynchronous. The object hierarchy is similar to D-Bus API described above.

-

Property Lists

Every server-side object has a Property List, a map with textual keys and arbitrary textual or binary values. Applications and modules may get and set these properties. Various modules implement automatic actions based on some properties, like routing, volume setup, and autoloading filters.

The typical usage in applications is to provide a property list when creating a context (for client properties) and when creating a stream (for stream properties). Higher-level frameworks that use PulseAudio (like GStreamer) usually do it automatically.

-

Operations

All operations with server-side objects are asynchronous. Many API calls return an Operation object which represents an asynchronous request. It may be used to poll the request status, set completion callback, or cancel the request.

-

Events

The client can receive two types of events from server:

-

subscription events

Events API provides methods for subscribing events triggered for the server-side objects available through the introspection API. Every event has an integer type and arbitrary binary payload.

-

stream events

Stream Events are generated to acknowledge the client of the stream state change or ask it to do something, e.g. pause the stream. Such event has a textual name and arbitrary binary payload.

-

Simple API

Simple API is a convenient wrapper around the threaded main loop and stream. The user just chooses parameters, connects to the server and writes or reads samples. All operations are blocking.

Limitations:

- only single stream per connection is supported

- no support for volume control, channel mappings, and events

Protocols and networking

PulseAudio server supports a variety of network protocols to communicate with clients, remote servers, and third-party software. See Network page on wiki.

PulseAudio implements two custom protocols:

- “native”, a full-featured protocol for most client-server and server-server communications

- “simple”, which is rarely useful

It also supports several foreign transport and discovery protocols:

- mDNS (Zeroconf)

- RTP/SDP/SAP

- RAOP

- HTTP

- DLNA and Chromecast

- ESound

And two control protocols:

- D-Bus API

- CLI protocol

Native protocol

PulseAudio uses a so-called “native” protocol for client-server and server-server connections, which works over a Unix domain or TCP stream socket. It is a rich, binary, message-oriented, bidirectional, asynchronous protocol.

The Asynchronous API described above mostly mirrors the features provided by this protocol.

They are:

- authentication - provide authentication data for the server

- streams - manage server-side stream state and exchange samples

- sample cache - manage server-side sample storage

- introspection - query and modify server-side objects

- events - subscribe server-side object events

- extensions - send custom commands to modules

There are four message types, each with a header and an optional payload:

-

packet

Control message. May contain a command (from client to server), a reply (from server to client), or an event (from server to client). Each message has its own payload type.

-

memblock

Data message. Contains a chunk of samples. In the zero-copy mode payload with samples is omitted and the message contains only a header.

-

shmrelease, shmrevoke

Shared pool management message. These messages are used to manage the shared memory pool employed in the zero-copy mode.

With the “native” protocol, the client is clocked by the server. Server requests client to send some amount of samples from time to time.

Since the protocol uses stream sockets, it’s not real time. The delays introduced by the sender or network cause playback delays on the receiver.

Zero-copy mode

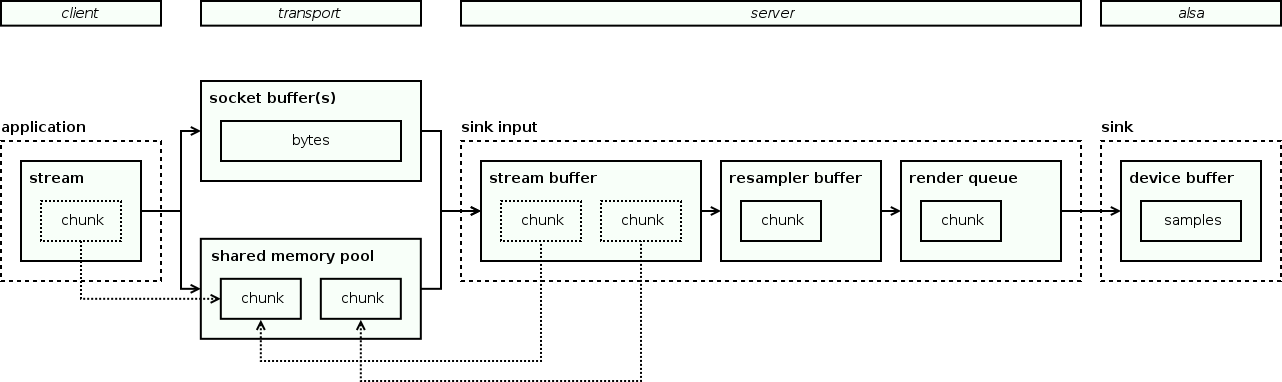

When the “native” protocol is used for client and server on the same host, the zero-copy mode may be employed.

It requires Unix domain socket to be used, and POSIX shared memory or Linux-specific memfd to be supported and enabled in PulseAudio. It also requires the server and client to run as the same user, for security reasons.

In this mode, chunks are allocated in a shared memory pool and communication is done through a shared ring buffer channel that uses a shared memory block for data and two file descriptor-based semaphores for notifications, on top of POSIX pipe or Linux-specific eventfd.

To establish communication, the server should send to the client file descriptors of the shared memory region and semaphores. The algorithm is the following:

- the server creates an anonymous in-memory file using

shm_open(POSIX) ormemfd_create(Linux-specific) - the server maps the file to memory using

mmapand initializes a memory pool there - the server allocates one block from the pool, initializes the shared ring buffer, and creates semaphores using

pipe(POSIX) ofeventfd(Linux-specific) - the server transfers file descriptors to the client via a Unix domain socket using

sendmsg, which provides special API for this feature - the client receives file descriptors and also maps the file to memory using

mmap - the server and client now use single shared memory pool and ring buffer

- to avoid races, the server and client use mutexes that are placed inside shared memory as well

After this, all messages (packet, memblock, shmrelease, shmrevoke) are sent via the shared ring buffer.

When the memblock message is sent in the zero-copy mode, it’s payload is omitted. Since the server and client use the same shared memory pool, the chunk payload can be obtained from the memory pool using the chunk identifier in the chunk header and is not needed to be transmitted.

Two additional messages are used in this mode:

- the peer that received a chunk sends

shmreleasewhen it finishes reading the chunk and wants to return it to the shared memory pool - the peer that has sent a chunk may send

shmrevokewhen it wants to cancel reading from the chunk

To achieve true zero-copy when playing samples, an application should use the Asynchronous API and delegate memory allocation to the library. When the zero-copy mode is enabled, memory is automatically allocated from the shared pool.

Authentication

When a client connects to the server via the “native” protocol, the server performs several authentication checks in the following order:

-

auth-anonymous

If the

auth-anonymousoption is set, then the client is accepted. -

uid

If a Unix domain socket is used, and the client has the same UID as the server, then the client is accepted. This check uses a feature of Unix domain sockets that provide a way to securely determine credentials of the other side.

-

auth-group

If a Unix domain socket is used, and the

auth-groupoption is set, and the client belongs to the group specified by this option, then the client is accepted. -

auth-cookie

If the

auth-cookieoption is set, and the client provided a correct authentication cookie, then the client is accepted.On start, the server checks a cookie file, usually located at

"~/.config/pulse/cookie". If the file isn’t writable, the server reads a cookie from it. Otherwise, it generates a new random cookie and writes it to the file. Optionally, the server also stores the cookie into the X11 root window properties.Client searches for a cookie in an environment variable, in the X11 root window properties, in parameters provided by the application, and in the cookie file (in this order).

-

auth-ip-acl

If TCP socket is used, and the

auth-ip-acloption is set, and client’s IP address belongs to the address whitelist specified in this option, then the client is accepted. -

reject

If all checks have failed, then the client is rejected.

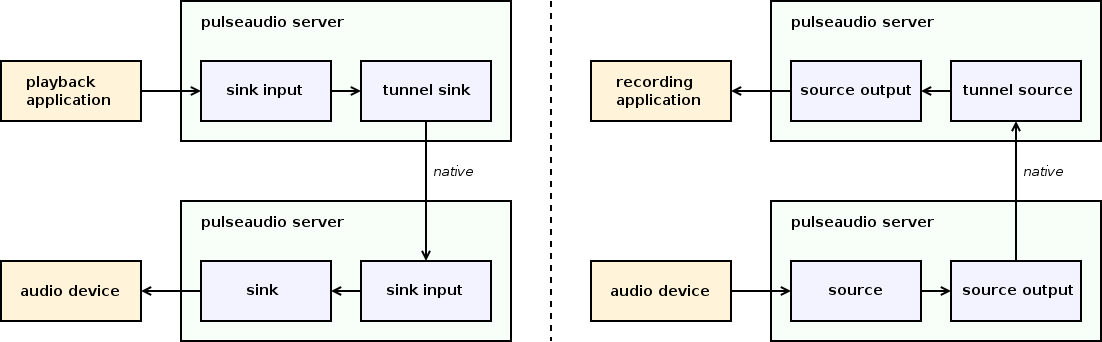

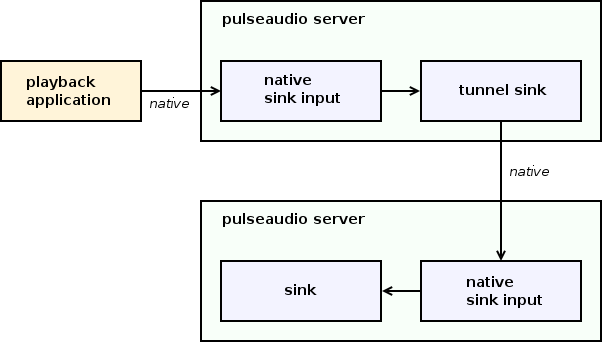

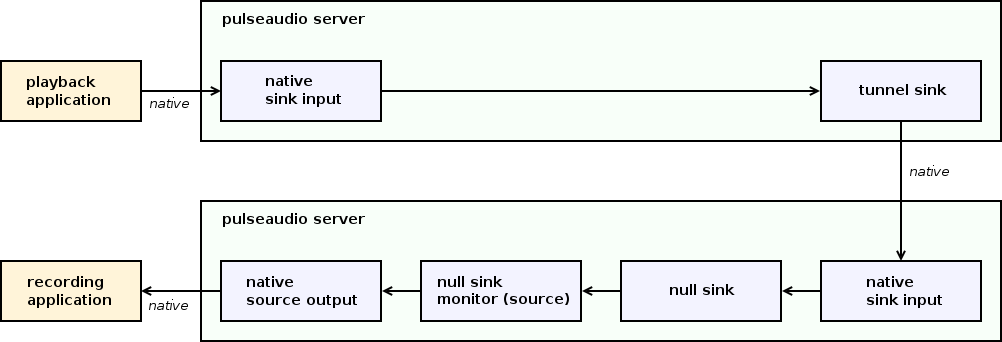

Tunnels

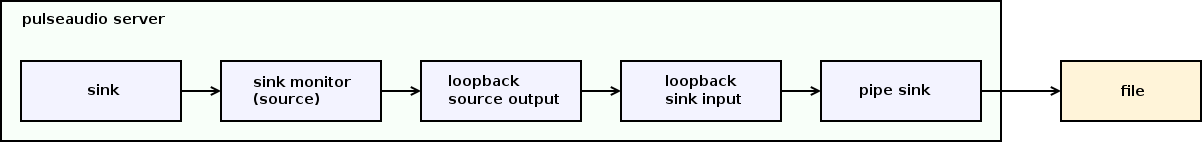

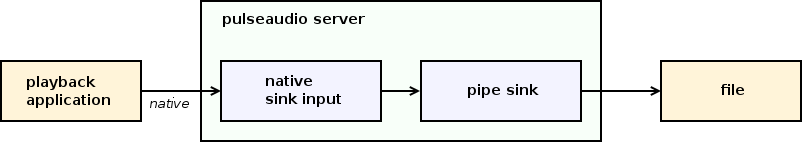

Local applications may be connected with to audio devices using tunnel sources and sinks. The diagram below illustrates an example of such connections.

Each tunnel connects a single pair of a local device and remote stream:

- a local tunnel sink is connected to a remote sink input

- a local tunnel source is connected to a remote source output

Each tunnel acts as a regular PulseAudio client and connects to a remote PulseAudio server via the “native” protocol over TCP. Tunnel sink creates a playback stream, and tunnel source creates a recording stream.

Tunnel devices may be created either manually by the user or automatically if the Zeroconf support is enabled.

mDNS (Zeroconf)

mDNS (multicast DNS) protocol, a part of the Zeroconf protocol stack, resolves names in the local network without using a name server.

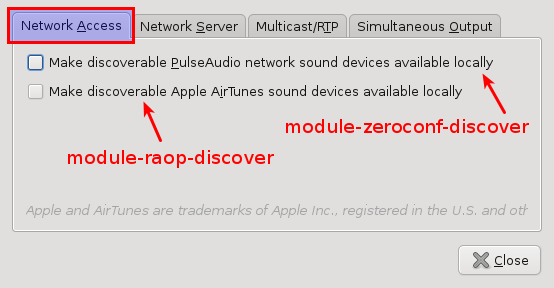

PulseAudio may use Avahi (free Zeroconf implementation) or Bonjour (Apple Zeroconf implementation). If Avahi or Bonjour daemon is running and the Zeroconf support is enabled in PulseAudio, every sink and source on every PulseAudio server in the local network automatically become available on all other PulseAudio servers.

To achieve this, PulseAudio uses automatically configured tunnels:

-

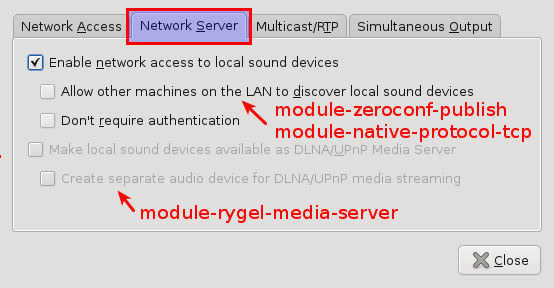

publishing

PulseAudio server publishes every sink and source as an mDNS service. Each published entry contains the server address, device name and type, and audio parameters, like sample rate and channel map.

Publishing is implemented for both Avahi (module-zeroconf-publish) and Bonjour (module-bonjour-publish).

-

discovery

PulseAudio server monitors services published on the local network. For every detected service, PulseAudio server creates a tunnel sink or source connected to the remote device and configured with the parameters of that device.

Discovery is implemented only for Avahi (module-zeroconf-discover).

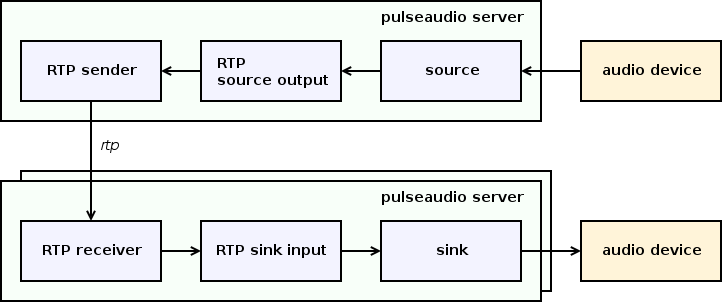

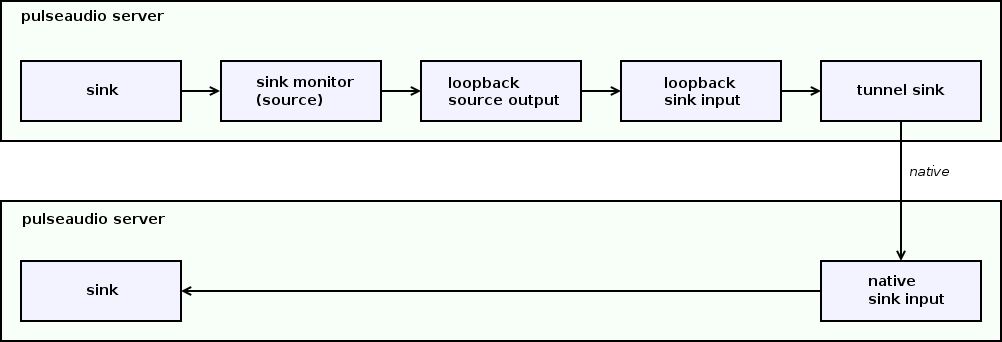

RTP/SDP/SAP

PulseAudio also has the RTP support. Unlike the “native” PulseAudio tunnels, this technology supports multicasting of a single local source to any number of remote sinks.

To achieve this, three protocols are used:

-

RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol)

A transport protocol for delivering audio and video over IP networks.

-

SDP (Session Description Protocol)

A format for describing multimedia session parameters. Usually used to describe RTP sessions.

-

SAP (Session Announcement Protocol)

A protocol for broadcasting multicast session information. Usually used to send SDP messages.

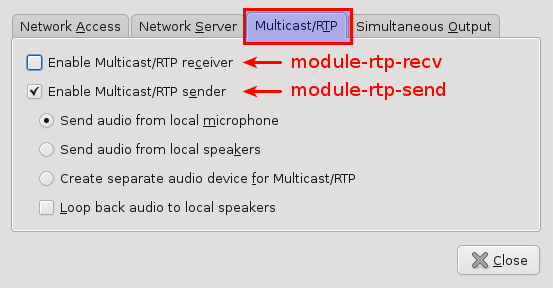

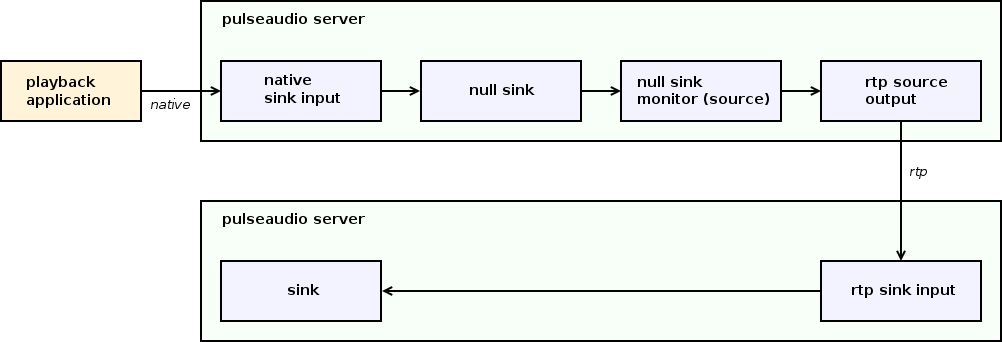

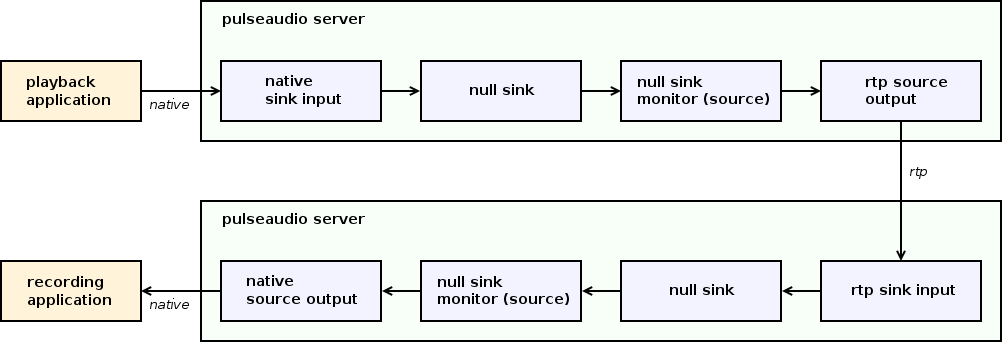

PulseAudio implements both RTP sender and receiver. They may be used together, or with other software that supports RTP, for example VLC, GStreamer, FFMpeg, MPLayer, or SoX. See RTP page on wiki.

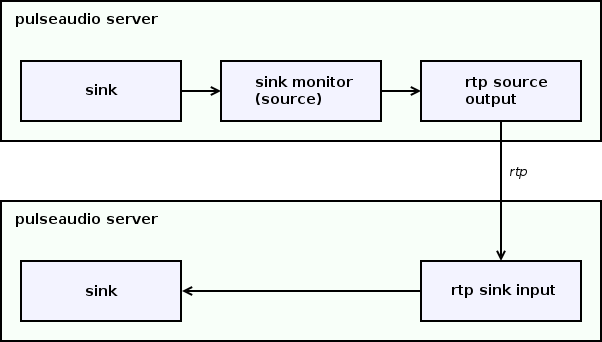

The diagram below shows an example workflow.

-

RTP sender

RTP sender creates an RTP source output.

Every RTP source output is connected to a single source and configured to send RTP packets to a single network address, usually a multicast one.

When the RTP source output is created, it broadcasts RTP session parameters to the local network using SDP/SAP. When source writes samples to RTP source output, source output sends them to preconfigured address via RTP. When RTP source output is destroyed, it broadcasts goodbye message using SDP/SAP.

-

RTP receiver

RTP receiver listens to SDP/SAP announcements in the local network.

When it receives an announcement for a new RTP session, it creates RTP sink input for it. When it receives goodbye message, it destroys the appropriate RTP sink input.

Every RTP sink input is connected to single sink and is configured to receive RTP packets from single RTP sender.

When RTP sink input receives an RTP packet, it stores it in the queue. When sink requests samples from RTP sink input, RTP sink input reads samples from that queue.

RTP sender can’t be clocked by RTP receiver because the sender has no feedback from the receiver and there may be multiple receivers for a single multicast sender. Since sender and receiver clocks are always slightly different, the receiver queue size is slowly drifting. To avoid this, RTP receiver adjusts resampler rate on the fly so that samples are played a bit slower or faster depending on the queue size.

RTP is a real time protocol. The delays introduced by the sender or network cause playback holes on the receiver. Playback is never delayed and packets delivered too late are just dropped.

RAOP (AirPlay)

RAOP (Remote Audio Output Protocol) is a proprietary streaming protocol based on RTP and RTSP, used in Apple AirPlay devices. RTP is a transport protocol, and RTSP is a control protocol.

AirPlay devices use mDNS and are discoverable via Zeroconf. AirPlay uses AES encryption, but the RSA keys were extracted from Apple devices, and open-source RAOP implementations appeared.

Since version 11.0, PulseAudio has built-in support for RAOP2. PulseAudio uses Avahi to receive mDNS RAOP announcements. Every AirPlay device in the local network automatically becomes available in PulseAudio.

RAOP support consists of two parts:

-

discovery

PulseAudio server monitors services published on the local network. For every detected service, PulseAudio server creates an RAOP sink.

-

sink

Every RAOP sink is connected to a single AirPlay device. It uses RTSP to negotiate session parameters and RTP to transmit samples.

HTTP support

The HTTP support provides two features:

-

web interface

A simple web interface provides a few bits of information about the server and server-side objects.

-

streaming

It’s possible to receive samples from sources and sink monitors via HTTP. This feature is used for DLNA support.

Every source or sink monitor has a dedicated HTTP endpoint.

When a new HTTP client connects to the endpoint, PulseAudio first sends the standard HTTP headers, including the “Content-Type” header with the MIME type corresponding to the sample format in use.

After sending headers, PulseAudio creates a new source output connected to the source or sink monitor which writes all new samples to the HTTP connection. Samples are sent as-is, without any additional encoding.

DLNA and Chromecast

DLNA (Digital Living Network Alliance) is a set of interoperability guidelines for sharing digital media among multimedia devices. It employs numerous control and transport protocols, including UPnP, RTP, and custom HTTP APIs.

Chromecast is a line of digital media players developed by Google. It uses Google Cast, a proprietary protocol stack, based on Google Protocol Buffers and mDNS.

There are two implementations of DLNA and/or Chromecast support:

-

module-rygel-media-server

PulseAudio can become a DLNA media server so that other DLNA devices can discover and read PulseAudio sources. This feature is implemented using Rygel, a DLNA media server. See details here.

PulseAudio registers a Rygel plugin, which exports PulseAudio sources and sink monitors via D-Bus. Every exported source or sink monitor includes an HTTP URL that should be used to read samples from PulseAudio.

For its part, Rygel publishes exported sources and sink monitors via UPnP, and ultimately DLNA clients may see them and read PulseAudio streams via HTTP.

-

pulseaudio-dlna

A third-party pulseaudio-dlna project allows PulseAudio to discover and send audio to DLNA media renderers and Chromecast devices. Devices published in the local network automatically appear as new PulseAudio sinks.

This project is implemented as a standalone daemon written in Python. The daemon creates a null sink for every discovered remote device, opens the sink monitor associated with it, reads samples from the monitor, performs necessary encoding, and sends samples to the remote device.

The communication with the PulseAudio server is done via the D-Bus API (to query and configure server objects) and

parectool (to receive samples from a sink monitor).

ESound

PulseAudio server may be accessed via the protocol used in Enlightened Sound Daemon.

The documentation says that it supports playback, recording, and control commands, so switching to PulseAudio should be transparent for applications that are using ESound.

Simple

The “simple” protocol is used to send or receive raw PCM samples from the PulseAudio server without any headers or meta-information.

The user should configure the sample format and the source and sink to use. Then the user may use tools like netcat to send PCM samples over a Unix domain or TCP socket.

CLI

PulseAudio server implements its own CLI protocol.

It is a simple text protocol that provides various commands to inspect and control the server:

- status commands - list and inspect server-side objects

- module management - load, unload, and inspect modules

- moving streams - move streams to devices

- killing clients and streams - remove clients and streams

- volume commands - setup volumes of devices and streams

- configuration commands - setup parameters of devices and device ports

- property lists - setup property lists of devices and streams

- sample cache - add, remove, or play samples in the server-side sample cache

- log and debug commands - configure logging, dump server configuration, etc

- meta commands - include and conditional directives

The same syntax may be used in several places:

- in PulseAudio configuration files

- over a Unix domain or TCP socket (module-cli-protocol-{unix,tcp})

- over the controlling TTY of the server (module-cli)

The TTY version requires that the server should be started in foreground mode in a terminal. The pacmd tool uses the CLI protocol over a Unix domain socket.

Device drivers

PulseAudio has several backends that implement audio I/O and device management. The diagram below illustrates backend-specific components.

-

card

A card represents a physical audio device, like a sound card or Bluetooth device. It contains card profiles, device ports, and devices. It has a single active card profile.

-

card profile

A card profile represents an opaque configuration set of a card, like an analog or digital mode. It defines the backend-specific configuration of the card, and the list of currently available device ports and devices.

-

device port

A device port represents a single input or output port on the card, like internal speakers or external line-out. Multiple device ports may belong to a card.

-

device

A device (source or sink) represents an active sample producer or consumer. A device is usually associated with a card and a set of device ports. It has a single active device port. Multiple devices may belong to a card.

Every backend should implement the following features of a source or sink:

- reading or writing samples to the device

- maintaining latency

- providing clocking in the device time domain

Currently, the only full-featured backends are ALSA and Bluetooth, which implement all object types listed above. Other backends provide only sources and sinks.

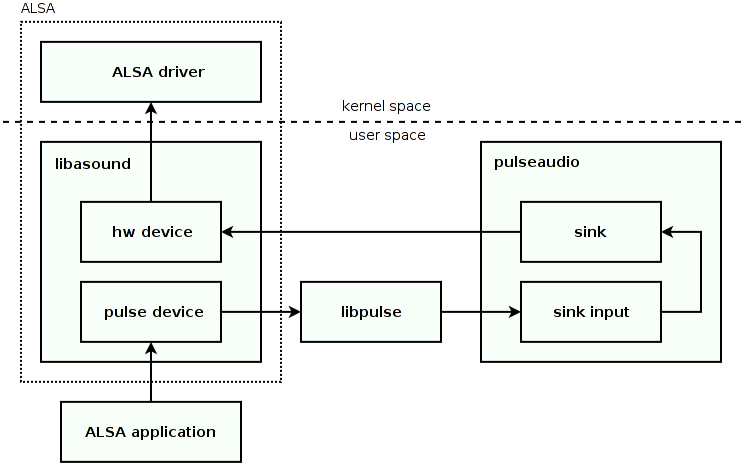

ALSA backend

ALSA (Advanced Linux Sound Architecture) is a Linux kernel component providing device drivers for sound cards, and a user space library (libasound) interacting with the kernel drivers. It provides a rich high-level API and hides hardware-specific stuff.

ALSA backend in PulseAudio automatically creates PulseAudio cards, card profiles, device ports, sources, and sinks:

-

PulseAudio card is associated with an ALSA card.

-

PulseAudio card profile is associated with a configuration set for an ALSA card. It defines a subset of ALSA devices belonging to a card, and so the list of available device ports, sources, and sinks.

-

PulseAudio device port is associated with a configuration set for an ALSA device. It defines a list of active inputs and outputs of the card and other device options.

-

PulseAudio source and sink are associated with an ALSA device. When a source or sink is connected to a specific device port, they together define an ALSA device and its configuration.

The concrete meaning of PulseAudio card profile and device ports depends on whether the ALSA UCM is available for an ALSA card or not (see below).

PulseAudio sources and sinks for ALSA devices implement a timer-based scheduler that manages latency and clocking. It is discussed later in a separate section.

ALSA device hierarchy

ALSA uses a device hierarchy that is different from the PulseAudio hierarchy. See this post for an overview.

The ALSA hierarchy has three levels:

-

card

ALSA card represents a hardware or virtual sound card. Hardware cards are backed by kernel drivers, while virtual cards are implemented completely in user space plugins.

-

device

ALSA card contains at least one playback or capture device. A device is something that is capable of processing single playback or recording stream. All devices or a card may be used independently and in parallel. Typically, every card has at least one playback device and one capture device.

-

subdevice

ALSA device contains at least one subdevice. All subdevices of the same device share the same playback or recording stream. For playback devices, subdevices are used to represent available slots for hardware mixing. Typically, there is no hardware mixing, and every device has a single subdevice.

ALSA device is identified by a card number and device number. PulseAudio by default interacts only with hardware ALSA devices. PulseAudio currently doesn’t use hardware mixing and so don’t employ multiple subdevices even if they’re available.

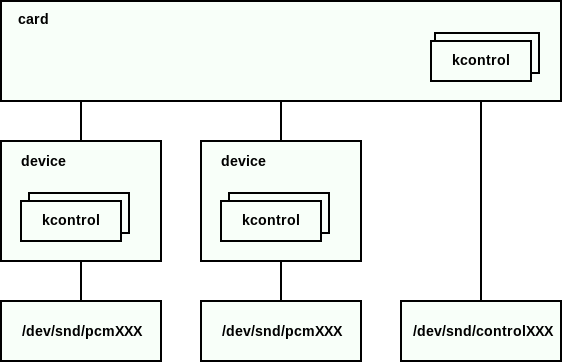

ALSA kernel interfaces

Each ALSA device has a corresponding device entry in the "/dev/snd" directory. Their meta-information may be discovered through the "/proc/asound" directory. See some details in this post.

The diagram below shows the device entries involved when PulseAudio is running.

Five device entry types exist:

-

pcm - for recording or playing samples

-

control - for manipulating the internal mixer and routing of the card

-

midi - for controlling the MIDI port of the card, if any

-

sequencer - for controlling the built-in sound synthesizer of the card, if any

-

timer - to be used in pair with the sequencer

PulseAudio interacts only with the pcm and control device entries.

Every ALSA card and device may have a set of kcontrols (kenrnel control elements) associated with it. The kernel provides generic operations for manipulating registered kcontrols using ioctl on the corresponding device entry.

A kcontrol has the following properties:

-

name - a string identifier of the kcontrol

-

index - a numerical identifier of the kcontrol

-

interface - determines what entity this kcontrol is associated with, e.g. “card” (for card kcontrols), “pcm” (for pcm device kcontrols) or “mixer” (for control device kcontrols)

-

type - determines the type of the kcontrol members, e.g. “boolean”, “integer”, “enumerated”, etc.

-

members - contain the kcontrol values; a kcontrol can have multiple members, but all of the same type

-

access attributes - determine various kcontrol access parameters

A kcontrol typically represent a thing like a volume control (allows to adjust the sound card internal mixer volume), a mute switch (allows to mute or unmute device or channel), a jack control (allows to determine whether something is plugged in, e.g. into an HDMI or a 3.5mm analog connector), or some device-specific option.

The concrete set of the available kcontrols are defined by the sound card driver, though drivers try to provide similar kcontrols. The driver usually just exposes all available hardware controls, and it’s up to the user space to provide a unified hardware-independent layer on top of them. This responsibility rests on the ALSA UCM and PulseAudio.

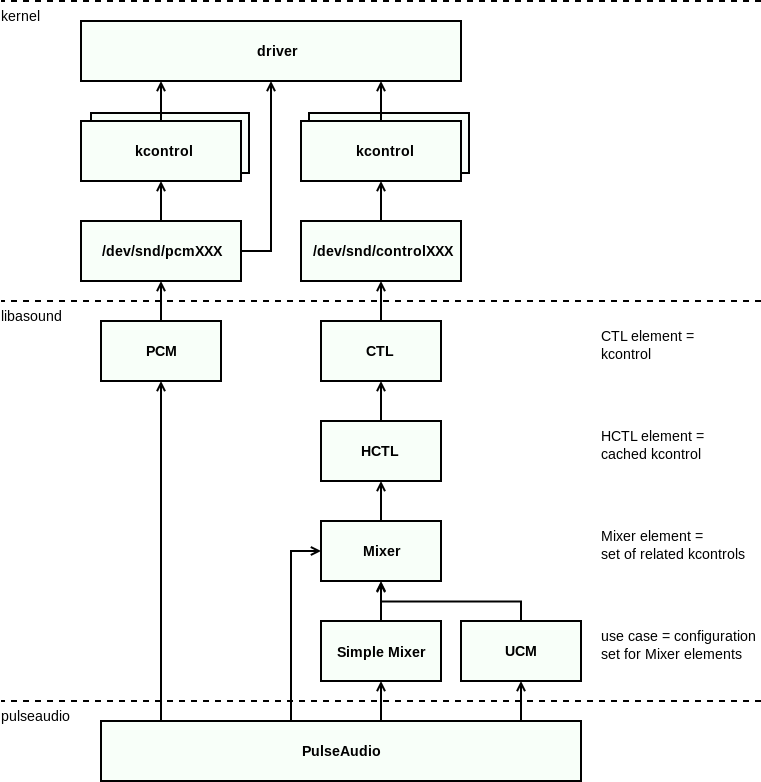

ALSA user space interfaces

ALSA provides numerous user space interfaces to interact with ALSA cards and devices and their properties. See libasound documentation: 1, 2.

The diagram below provides an overview of the components involved when PulseAudio is running.

Here is the list of involved ALSA interfaces:

-

PCM

PCM interface implements methods for playback and recording on top of the pcm device entry.

Applications can setup the per-device kernel-side ring buffer parameters, write or read samples to the buffer, and issue flow control operations.

This interface is used in most ALSA applications.

-

CTL

CTL interface implements low-level methods for accessing kcontrols on top of the kernel ioctl API.

Applications can inspect, read, and write CTL elements, which are mapped one-to-one to the kernel-side kcontrols.

This interface is usually not used directly.

-

HCTL

HCTL interface implements a caching layer on top of the CTL interface.

Applications can inspect, read, and write HCTL elements, mapped one-to-one to the CTL elements, and in addition, can set per-element callbacks for various events.

This interface is usually not used directly.

-

Mixer

Mixer interface implements a higher-level management layer above the HCTL interface.

It provides a framework for managing abstract mixer elements. A mixer element is, generally speaking, a set of logically grouped HCTL elements. Applications register custom mixer element classes and implement a custom mapping of the HCTL elements to the mixer elements.

This interface provides a generic and rather complex asynchronous API. In most cases, applications may use the Simple Mixer interface instead.

-

Simple Mixer

Simple Mixer interface implements a mixer element class for the Mixer and provides a simple and less abstract synchronous API on top of it.

A Simple Mixer element represents a logical group of the related kcontrols. An element may have the following attributes, mapped internally to the corresponding HCTL elements: a volume control, a mute switch, or an enumeration value. Each attribute may be playback, capture, or global. Each attribute may be also per-channel or apply to all channels.

This interface is supposed to be used by applications that want to control the mixer and do not need the complex and generic Mixer API.

-

UCM

UCM (Use Case Manager) interface implements high-level configuration presets on top of the Mixer interface.

Applications can describe their use-cases by selecting one of the available presets instead of configuring mixer elements manually. The UCM then performs all necessary configuration automatically, hiding machine-specific details and complexity of the Mixer interface.

ALSA routing

ALSA cards often have multiple inputs and outputs. For example, a card may have an analog output for internal speaker, an analog output for 3.5mm headphone connector, an analog input for internal microphone, an analog input for 3.5mm microphone connector, and an HDMI input and output.

ALSA interfaces represent this in the following way:

-

an ALSA card contains separate ALSA devices for HDMI and analog audio

-

an ALSA device has separate pcm device entries in

"/dev/snd"for playback and capture -

an ALSA card has a control device entry in

"/dev/snd"with various kcontrols allowing to determine what’s plugged in and configure input and output routing

The following kcontrols may be used:

-

jack controls

Jack controls may be used to determine what’s plugged in. Drivers usually create jack controls for physical connectors, however, details may vary.

For example, headphone and microphone connectors may be represented with a single jack control or two separate jack controls. An internal speaker or microphone can be sometimes represented with a jack control as well, despite the fact that there is no corresponding physical connector.

-

mute controls

Mute controls may be used to mute and unmute a single input or output. Drivers usually create mute controls for every available input and output of a card.

-

route controls

An enumeration control may be sometimes provided to choose the active input or output.

Different drivers provide different sets of kcontrols, and it’s up to the user space to build a unified hardware-independent layer on top of them. PulseAudio is able to do it by itself, or alternatively may rely on ALSA UCM.

In both cases, PulseAudio goal is to probe what inputs and outputs are available and map them to device ports somehow. However, details vary depending on whether UCM is in use or not.

ALSA cards with UCM

ALSA Use Case Manager aims two goals:

-

Abstract the applications which configure ALSA devices from the complexity of the Mixer interface.

-

Make these applications portable across numerous embedded and mobile devices, by moving the machine-specific part to configuration files.

UCM lets applications to operate with such high-level operations as “setup this device to play HiFi music via an external line-out” or “setup that device to capture voice for a phone call via an internal microphone”.

UCM then looks into the local configuration files and maps such use-case description to the concrete values of mixer elements. These files may be part of the UCM package or may be provided by a device vendor.

An application provides the UCM with three strings:

-

ucm verb

Defines the main operation mode of an ALSA device, e.g. “HiFi” or “Voice”. Only one UCM verb may be active at the same time.

-

ucm modifier

Defines a supplementary operation mode of an ALSA device, e.g. “PlayMusic” or “PlayTone”. Available UCM modifiers are defined by currently active UCM verb. Zero or multiple UCM modifiers may be active at the same time.

-

ucm device

Defines configuration of active inputs and outputs of an ALSA device, e.g. “Speaker” or “Headset”. Available UCM devices are defined by currently active UCM verb. Zero or multiple UCM devices may be active at the same time.

A combination of one UCM verb, zero or multiple UCM modifiers, and one or multiple UCM devices define what ALSA device to use and how to configure its mixer elements.

When UCM is available for a card, PulseAudio automatically employs it.

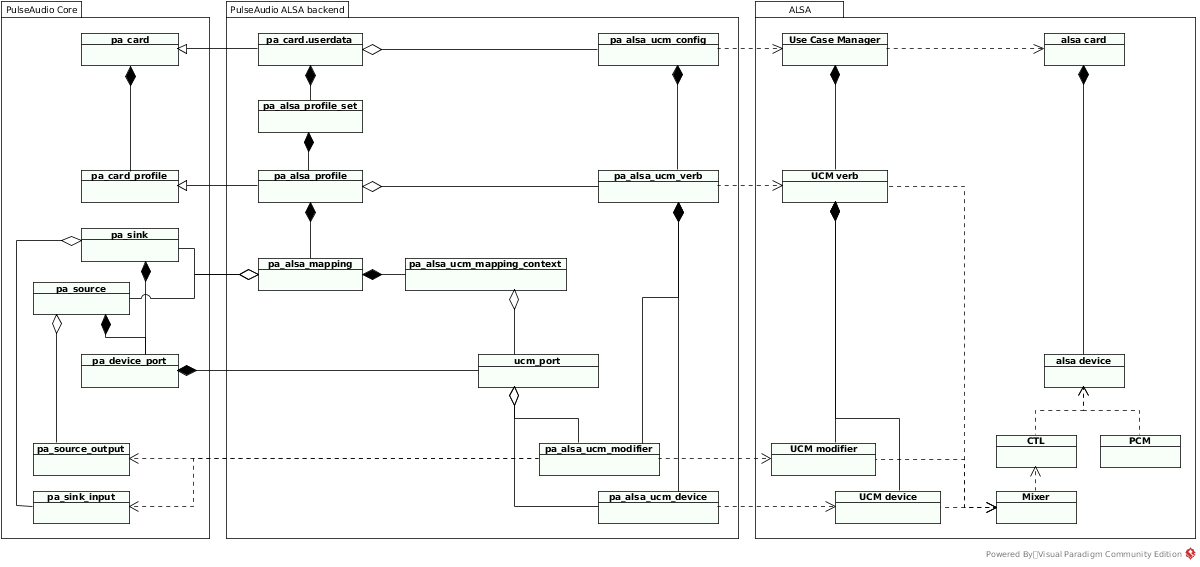

The diagram below illustrates relations between PulseAudio and ALSA objects when the UCM is active. Some diagrams and details are also available on Linaro Wiki: 1, 2, 3.

The mapping of the PulseAudio object hierarchy to the ALSA object hierarchy is the following:

-

PulseAudio card is associated with the UCM interface of an ALSA card. One PulseAudio card is created for every ALSA card.

-

PulseAudio card profile is associated with a UCM verb. For every card, one PulseAudio profile is created for every UCM verb available for the card.

-

PulseAudio source is associated with the PCM interface of a capture ALSA device. For every card, one PulseAudio source is created for every available capture ALSA device that is associated with a UCM verb, UCM modifier, or UCM device available in the currently active card profile.

-

PulseAudio sink is associated with the PCM interface of a playback ALSA device. For every card, one PulseAudio sink is created for every playback ALSA device that is associated with a UCM verb, UCM modifier, or UCM device available in the currently active card profile.

-

PulseAudio device port is associated with a combination of a UCM modifier and UCM devices. For every source or sink, one PulseAudio device port is created for every possible valid combination of zero or one UCM modifier and one or multiple UCM devices.

A valid combination includes:

- only UCM modifiers and devices that are enabled by currently active card profile

- only UCM modifiers and devices that are associated with the ALSA device of the source or sink

- only non-mutually exclusive UCM devices

Every UCM modifier is mapped to a PulseAudio role. The UCM modifier of a device port is actually enabled only when there is at least one source output or sink input connected to the source or sink of the device port, which has a “media.role” property equal to the UCM modifier’s role.

This is how the mapping is used:

-

The card defines what ALSA card is used, and so what profiles are available.

-

The currently active card profile of the card defines what UCM verb is used, and so what sources and sinks are available.

-

The source or sink defines what ALSA device is used, and so what device ports are available.

-

The currently active device port of the source or sink defines what UCM modifier and UCM devices are used. Whether the UCM modifier is enabled depends on the roles of currently connected source outputs or sinks inputs.

-

The currently active UCM verb, UCM modifier, and UCM devices define what card inputs and outputs are active, what device options are set, and what volume controls are used.

ALSA cards w/o UCM

Besides the UCM support, PulseAudio has its own configuration system on top of the ALSA Mixer. It was developed before UCM appeared. It is used when the UCM is not available for a card.

Mixer configuration is described in custom PulseAudio-specific configuration files. See Profiles page on wiki.

Configuration files define the following objects:

-

profile set

Provides available profiles for an ALSA card. Contains a list of profiles.

Physically it is a

.conffile under the"/usr/share/pulseaudio/alsa-mixer/profile-sets"directory. -

profile

Represents a configuration set for an ALSA card. Contains a list of mappings.

Every mapping defines a playback or capture ALSA device that is available when this profile is active, and the configuration sets available for each device.

Physically it is a

[Profile]section in the profile file. -

mapping

Represents a playback or capture ALSA device. Contains:

-

device strings

Device string is a pattern used to match an concrete ALSA device belonging to the ALSA card. First matched device is used.

-

channel map

Channel mapping defines what channels are used for the ALSA device.

-

input/output paths

Mapping contains multiple input and output paths that represent alternative configuration sets for the ALSA device.

Every input or output path defines a single configuration set, which provides an ALSA mixer path and settings for ALSA mixer elements accessible through that path.

Physically it is a

[Mapping]section in the profile file. -

-

path

Represents a configuration set for a single capture or playback ALSA device. Contains a list of elements, and a list of jacks.

Every element or jack defines an ALSA mixer element and how it should be used when the configuration set defined by this path is active.

Physically it is a

.conffile under the"/usr/share/pulseaudio/alsa-mixer/paths"directory. -

jack

Represents an ALSA mixer element for a jack that should be used for probing. Contains identifier of the ALSA mixer element and its expected state (plugged or unplugged).

Every jack is probed and its state is compared with the expected one. This probing is used to activate only those paths that are actually available.

Physically it is a

[Jack]section in the path file. -

element

Represents an ALSA mixer element and defines how it should be handled. Contains:

-

element id

Defines the name of the ALSA mixer element.

-

volume policy

Defines how to handle the volume of the ALSA mixer element. It may be either ignored, unconditionally disabled, unconditionally set to a constant, or merged into the value of PulseAudio volume slider.

-

switch value

Defines how to handle the value of a switch ALSA mixer element. It may be either ignored, unconditionally set to a constant, used for muting and unmuting, or made selectable by the user via an option.

-

enumeration value

Defines how to handle the value of enumeration ALSA mixer element. It may be either ignored, or made selectable by the user via an option.

-

options

Every option defines one alternative value of a switch or enumeration ALSA mixer element. This value is made selectable by the user.

Physically it is an

[Element]section in the path file. -

-

option

Represents one alternative value of a switch or enumeration ALSA mixer element. Contains identifier of the ALSA mixer element and its value.

Physically it is an

[Option]section in the path file.

When UCM is not available for a card, PulseAudio uses Udev rules to select an appropriate profile set for the card:

-

PulseAudio installs Udev rules that match known audio card devices by vendor and product identifiers and set

PULSE_PROFILE_SETproperty for them. The property contains a name of a profile set.conffile. -

When PulseAudio configures a new ALSA card that has no UCM support, it reads the

PULSE_PROFILE_SETproperty set by Udev rules and loads the appropriate profile set file. The file defines how to create and configure card profiles, device ports, sources, and sinks. -

If an ALSA card was not matched by Udev rules and the

PULSE_PROFILE_SETproperty was not set, PulseAudio uses default profile set which contains some reasonable configuration for most cards.

The diagram below illustrates relations between PulseAudio and ALSA objects when UCM is not used.

The mapping of the PulseAudio object hierarchy to the ALSA object hierarchy is the following:

-

PulseAudio card is associated with an ALSA card and a profile set defined in configuration files. One PulseAudio card is created for every ALSA card, and one profile set is selected for every card.

-

PulseAudio card profile is associated with a profile defined in configuration files. For every card, one PulseAudio profile is created for every profile in the profile set of the card.

-

PulseAudio source is associated with a mapping defined in configuration files, and with the PCM interface of the capture device matched by the device mask of the mapping. For every card, one PulseAudio source is created for every mapping in the currently active profile.

-

PulseAudio sink is associated with a mapping defined in configuration files, and with the PCM interface of the playback device matched by the device mask of the mapping. For every card, one PulseAudio sink is created for every mapping in the currently active profile.

-

PulseAudio device port is associated with a combination of a path and options defined in configuration files. For every source or sink, one PulseAudio device port is created for every possible combination of one path and a subset of all options of all elements of this path.

This is how the mapping is used:

-

The card defines what ALSA card is used and what profile set is used, and so what profiles are available.

-

The currently active card profile of the card defines what mappings are available, and so what sources and sinks are available.

-

The source or sink defines what ALSA device is used, and what mapping is used, and so what device ports are available.

-

The currently active device port of the source or sink defines what path is used, what jacks are probed, what elements are used for getting and setting volume and how, and what combination of options of elements of the path is used.

-

The currently active elements, their volume policies, and their options define how to configure ALSA mixer elements of the ALSA device.

Bluetooth backend

PulseAudio supports Bluetooth, a wireless protocol stack for exchanging data over short distances. See Bluetooth page for details. PulseAudio relies on two backends for Bluetooth support:

Bluetooth specification defines numerous Bluetooth profiles which may be supported by a device. Each profile describes the protocols, codecs, and device roles to be used. A Bluetooth device may support a subset of defined profiles and roles. Note that Bluetooth profiles and roles are different from the PulseAudio card profiles and stream roles.

PulseAudio supports three Bluetooth profiles:

-

A2DP (Advanced Audio Distribution Profile)

Profile for high-quality audio streaming. Usually used to stream music.

The roles of the two connected A2DP devices are:

- Source role (SRC) - the device that sends audio

- Sink role (SNK) - the device that receives audio

PulseAudio supports both roles. For every discovered A2DP device, two options are available:

- for SRC device, the server may create a single PulseAudio source which acts as an SNK device

- for SNK device, the server may create a single PulseAudio sink which acts as an SRC device

-

HSP (Headset Profile)

Profile for phone-quality audio playback and recording. Usually used for phone calls.

The roles of the two connected HSP devices are:

- Headset role (HS) - the device with the speakers and microphone, e.g. a headset

- Audio Gateway role (AG) - the device that serves as a gateway to an external service, e.g. a mobile phone connected to a cellular network

PulseAudio supports both roles. It can communicate with a headset or be a headset itself for other device. For every discovered HS or AG device, the server may create a pair of PulseAudio source and sink which together act as an AG or HS device.

-

HFP (Hands-Free Profile)

Provides all features of HSP plus some additional features for managing phone calls.

The roles of the two connected HFP devices are:

- Hands-Free Unit role (HF) - the device with the speakers and microphone, e.g. a portable navigation device

- Audio Gateway role (AG) - the device that serves as a gateway to an external service, e.g. a mobile phone connected to a cellular network

PulseAudio supports both roles. It can communicate with a HF unit or be a HF unit itself for other device. For every discovered HF or AG device, the server may create a pair of PulseAudio source and sink which together act as an AG or HF device.

PulseAudio card profile is associated with a Bluetooth profile and role. The following card profiles are available:

-

High Fidelity Playback (A2DP Sink) - the PulseAudio card will provide a single PulseAudio source which acts as an A2DP SNK device

-

High Fidelity Capture (A2DP Source) - the PulseAudio card will provide a single PulseAudio sink which acts as an A2DP SRC device

-

Headset Head Unit (HSP/HFP) - the PulseAudio card will provide a pair PulseAudio source and sink which together act as an HF device

-

Headset Audio Gateway (HSP/HFP) - the PulseAudio card will provide a pair PulseAudio source and sink which together act as an AG device

Bluetooth backend listens to BlueZ and oFono events on D-Bus and automatically creates PulseAudio cards, sources, and sinks for all discovered Bluetooth devices.

The mapping of the PulseAudio object hierarchy to the Bluetooth object hierarchy is the following:

-

PulseAudio card is associated with a Bluetooth device. One PulseAudio card is created for every discovered Bluetooth device.

-

PulseAudio card profile is associated with a Bluetooth profile and role. One of the predefined PulseAudio card profiles created for every available operation mode supported by the Bluetooth device.

-

One PulseAudio source and/or one PulseAudio sink is created for every PulseAudio card depending on the currently active card profile.

-

One PulseAudio device port is created for every PulseAudio source or sink.

This is how the mapping is used:

-

The card defines what Bluetooth device is used and what profiles are available.

-

The currently active card profile defines what Bluetooth profile and role are used, and so what transport protocols and codecs are used.

JACK backend

JACK (JACK Audio Connection Kit) is a professional sound server that provides realtime low-latency connections between applications and hardware. Like PulseAudio, JACK may work on top of several backends, including ALSA.

However, their design goals are different. See comments from PulseAudio authors and JACK authors:

-

PulseAudio design is focused on consumer audio for desktop and mobile. It offers seamless device switching, automatic setup of hardware and networking, and power saving. It can’t guarantee extremely low latency. Instead, it usually adjusts latency dynamically to provide lower battery usage and better user experience even on cheap hardware.

-

JACK design is focused on professional audio hardware and software. It offers the lowest possible latency and may connect applications directly to devices or each other. It doesn’t try to provide the smooth desktop experience to the detriment of performance or configurability and is targeted to advanced users.

There are three alternative options to use PulseAudio and JACK on the same system:

- Use them for different sound cards. JACK can ask PulseAudio to release an ALSA card via device reservation API.

- Suspend PulseAudio when JACK is running using pasuspender tool.

- Configure PulseAudio to use JACK backend instead of ALSA.

JACK backend for PulseAudio monitors when JACK is started using the JACK D-Bus API, and then creates one source and sink that read and write samples to JACK.

PulseAudio uses two threads for a JACK source or sink: one realtime thread for the JACK event loop, and another for the PulseAudio one. The reason for an extra thread is that it’s not possible to add custom event sources to the JACK event loop, hence PulseAudio event loop can’t be embedded into it. The extra thread costs extra latency, especially if PulseAudio is not configured to make its threads realtime using rtkit.

Other backends

The following backends are available but have limited functionality:

-

OSS

componentmodule-detectmodule-ossOSS (Open Sound System) is an older interface for making and capturing sound in Unix and Unix-like operating systems. Nowadays it is superseded by ALSA on Linux but is used on some other Unix systems. Many systems, including Linux and various *BSD variants, provide a compatibility layer for OSS applications.

OSS backend implements source and sink for OSS devices. Each one is connected to a single device, usually

/dev/dspN. At startup, PulseAudio can automatically create a sink and source for every available OSS device. -

Solaris

componentmodule-detectmodule-solarisSolaris backend implements source and sink for

/dev/audiodevice available in Solaris and some *BSD variants, also known as “Sun audio” or “Sunau” and originally appeared in SunOS. This device supports the Au file format.At startup, PulseAudio can automatically create one sink and one source for

/dev/audiodevice if it is present. -

CoreAudio

componentmodule-coreaudio-{detect,device}CoreAudio is a low-level API for dealing with sound in Apple’s MacOS and iOS operating systems.

CoreAudio backend monitors available devices and automatically creates card, sink, and source for every detected device. No card profiles and device ports are implemented.

-

WaveOut

componentmodule-detectmodule-waveoutWaveOut backend implements source and sink for the legacy Win32 WaveIn/WaveOut interfaces. They are part of MultiMedia Extensions introduced in Windows 95 and still supported in recent Windows versions (with some issues).

Each source or sink is connected to a single device. At startup, PulseAudio can automatically create one sink and one source for the first available device if it is running on Windows.

-

ESound

componentmodule-esound-sinkESound backend implements a sink acting as a client for Enlightened Sound Daemon. It doesn’t implement source. The documentation recommends avoiding using this sink because of latency issues.

Note that PulseAudio server is also able to emulate ESound server.

Hotplug support

Hotplug is currently implemented for the following backends:

- ALSA (using libudev)

- Bluetooth (using BlueZ)

- JACK (using D-Bus JACK API)

- CoreAudio

In particular, PulseAudio uses libudev to detect ALSA cards (both with and without UCM support). The server creates Udev monitor and filters events for sound card devices:

- when a new device is inserted, the server creates a card, card profiles, device ports, sources, and sinks, as described above

- when the device is removed, all these objects are removed as well

Hardware controls

PulseAudio server has support for hardware controls. The user should manually specify a sink, and the server will forward volume up/down and mute requests to it.

Two types of controls are supported:

-

IR remote control

componentmodule-lircInfrared remote controls are handled using LIRC (Linux Infrared Remote Control).

-

Multimedia buttons

componentmodule-mmkbd-evdevMultimedia buttons available on some keyboards are handled using evdev, a generic input event interface in the Linux kernel, usually used in programs like X server and Wayland.

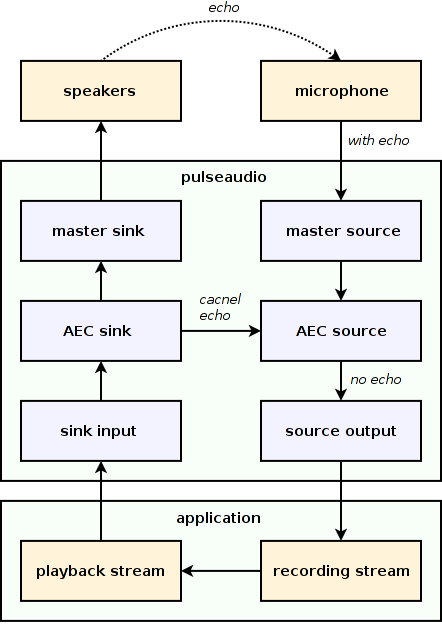

Sound processing

PulseAudio implements various sound processing tools. Some of them are enabled automatically when necessary (like sample rate conversion), and others should be explicitly configured by the user (like echo cancellation).

Resampler

Every source, sink, source output, and sink input may use its own audio parameters:

- sample format (e.g. 32-bit floats in native endian)

- sample rate (e.g. 44100Hz)

- channel map (e.g. two channels for stereo)

Source output and sink input are responsible for performing all necessary conversions when they are invoked by source or sink. To achieve this, they configure resampler with appropriate input and output parameters and then run it frame-by-frame.

When resampler is configured, it tries to select an optimal conversion algorithm for requested input and output parameters:

- chooses sample rate conversion method

- chooses the working sample format for sample rate conversion (some methods benefit from using a higher precision)

- calculates channel mapping (taking into account channel names and meaning)

For every frame, resampler performs the following steps:

- converts frame from input sample format to working sample format

- maps input channels to output channels

- converts sample rate from input rate to output rate

- if LFE channel (subwoofer) is used, applies the LR4 filter

- converts frame from working sample format to output sample format

Each step is performed only if it’s needed. For example, if input sample format and working sample format are the same, no conversion is necessary.

Sample rate conversion usually operates at fixed input and output rates. When a client creates a stream, it may enable variable rate mode. In this case, input or output rate may be updated on the fly by explicit client request.

The user can specify what method to use in the server configuration files. You can find a comparison of hardware and some software resampler methods in this post.

The following methods are supported:

-

speex

Fast resampler from Speex library. If PulseAudio was built with speex support, used by default.

-

ffmpeg

Fast resampler from FFmpeg library. If PulseAudio was built without speex support, and variable rate mode is not requested, used by default.

-

src

Slower but high-quality resampler from Secret Rabbit Code (libsamplerate) library. Used in some PulseAudio modules.

-

sox

Slower but high-quality resampler from SoX library. Not used by default.

-

trivial

Built-in low-quality implementation used as a fallback when PulseAudio was built without speex support, and ffmpeg can’t be used because variable rate mode was requested.

Instead of interpolation, it uses decimation (when downsampling) or duplication (when upsampling).

-

copy

No-op implementation used when input and output sample rates are the same.

-

peaks

Pseudo resampler that finds peaks. It is enabled when a client requests peak detection mode. Instead of interpolation, it calculates every output sample as a maximum value in the corresponding window of input samples.

This mode is usually used in GUI applications like

pavucontrolthat want to display volume level.

Mixing and volumes

When multiple sink inputs are connected to one sink, sink automatically mixes them, taking into account per-channel volume settings. See Volumes and Writing Volume Control UIs pages.

Every source, sink, sink input, and source output has its own per-channel volume level that may be controlled via both C API and D-Bus API.